Quick Summary of the case: a maker of t-shirts and hats applied to register two trademarks: THE HOUSE THAT JUICE BUILT and the logo shown below. The New York Yankees, owner of the trademark THE HOUSE THAT RUTH BUILT and a logo that includes a baseball with a stars and stripes hat, asked the TTAB not to register the t-shirt maker’s trademarks because the marks were confusingly similar to the Yankees’ marks.

First of all, what is a famous mark and why should a trademark owner care about achieving a further status for their mark beyond registration? Famous marks are those marks that have become so well-known to consumers far and wide that the mark is “untouchable”, meaning that visually similar trademarks cannot be used by third-parties for any other kinds of goods or services, regardless of whether the goods and services actually compete with those designated by the famous mark. Famous marks are the holy grail of trademark law precisely because they are so hard for the owner to get. The owner has to use a mark exclusively for many years and the public has to draw a strong connection between the trademark owner and the mark. This association has to be strong enough that the public would lose respect for the mark if it was used on goods outside those that the trademark owner has been using the mark on. Names like Tiffany’s, Rolex, Nike, and Exxon have achieved this famous mark status. Allowing anybody else to use these names (such as “Tiffany’s” for a plumbing service) would take away from the “special status” of the name Tiffany’s as a mark of luxury and timeless jewelry/fashion/etc.

So having a trademark designated as famous is “kind of a big deal,” as Ron Burgundy would say. The catch for trademark owners is that it is very hard to demonstrate that a mark has risen to such regard in society that it should be regarded as famous. Many trademark owners who seemed to have the legal chops to win have recently lost their bids to label their mark as famous (COACH for handbags and leather goods is a notable example). In general, a trademark owner has to show that the brand being asserted as famous reached a significant segment of consumers, including consumers who are not potential purchasers of the product. Usually recognition on the order of 75% or more is required, depending on the court conducting the analysis. There are of course other factors that go into establishing this market recognition (decades of trademark use, millions or billions of dollars in sales under the mark, and lots of unsolicited media attention).

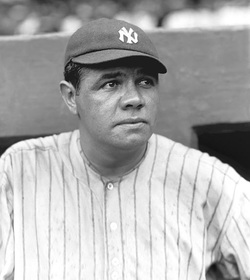

Back to the N.Y. Yankees. The Yankees were asserting that the phrase “The House That Ruth Built”, a phrase coined during the 1920s by a sportswriter as a nickname for Yankee Stadium, a stadium since demolished for Yankee Stadium II (which is, ironically, named “The House That Jeter Built”), to commemorate the date that Yankee Stadium opened and Babe Ruth hit a game-winning homerun. Over the years since, the phrase has stuck and been used continuously in connection with Yankee Stadium. Only recently (1996, according to the N.Y. Yankees trademark filings with the USPTO) have the N.Y. Yankees actually used the phrase in connection with goods and services.

One would think that a trademark would need to be used in a commercial sense on actual goods or services before it can even function as a trademark, never mind the additional requirement that the mark further be used for a number of years, and be the subject of millions of dollars of sales before it can achieve fame. Using a phrase in connection with a stadium, while it might build a reputation for the stadium itself, is not an actual trademark use. Instead, phrase is more a statement of the origin of the stadium and perhaps an era from the team’s history; it’s harder to see how such a phrase can be attributed to any one entity as a source for actual goods and services. Apparently, the Yankees did not produce any actual evidence showing that the phrase “The House That Ruth Built” was famous for designating the Yankees as the source of goods and services. Instead, the TTAB found applicant’s admission that the phrase was famous for designating Yankee Stadium as a baseball venue was sufficient. In other words, simply because the media and the general public have used the phrase repeatedly to refer to Yankee Stadium, that phrase can now be used by the Yankees to prevent any other uses. Poof: a famous trademark is born

The problem with the TTAB’s ruling is that it appears to recognize a phrase that has no source-identifying characteristics, at least as a famous mark attached to goods and services. The TTAB seemed to gloss over this distinction and instead focused on the fact that a mark can become famous regardless of who uses it. For example, the TTAB cited the mark BIG BLUE and the fact that the company itself was not responsible for coining the phrase as support for the claim that a mark owners’ use of the famous mark is not the end-all be-all. Of course, this reference ignores the fact that references to “Big Blue” in the realm of technology and computers; that is, the mark was actually used to reference goods and services of IBM. “The House That Ruth Built”, on the other hand, simply referred to a baseball stadium not a goods or services offered by an organization or even the organization itself. Indeed, the applicant for THE HOUSE THAT JUICE BUILT mark asserted this in testimony before the TTAB and made the same distinction in answers to questions posed by the Yankees during the discovery phase of the opposition.

Under the Yankees proposed framework for acquiring fame, complemented by commentary of the TTAB, the most important question to ask is how widely-known is a particular mark or phrase. The TTAB won’t concern itself with the specifics like how the phrase has been used over time by the person/entity asserting it as a trademark, and whether it was actually used as a trademark. Without some kind of connection to actual goods and services offered in commerce, phrases threaten to take on extra-trademark powers and scope, like creating a monopoly for the owner of the phrase across all mediums even where there is no commercial significance tied to the phrase “The House That Ruth Built”.

Takeaways from this interchange extend to two classes of trademark owners: (1) those asserting that a particular mark is famous, and (2) people seeking to make light of a phrase that has been used by one group of people or another to loosely refer to a single source (whether that source is a building, organization, or person).

For owners of famous marks, a trademark registration is not the end of the story, nor should some phrase that is loosely affiliated with your organization be counted on as actually designating a source. The trademark owner has to carefully consider all of the goods and services that a mark will designate and actually use the mark on those goods (and use it in a way that can be clearly articulated, not “the mark was used on the stadium marque, and baseball services were offered at the stadium). Moreover, if the trademark owner wants to make sure that its mark becomes well-regarded, it must make sure it garners attention for the mark outside the commercial norm of simply putting it on products and advertising. Drumming up media attention and generating consumer buzz will be beneficial. The idea is to try and shore up your use of the mark so it isn’t vulnerable to some kind of attack when you argue that the mark is famous. As Mr. Coleman wrote in his post, you want to bring the juice.

For people trying to use a mark that is similar to a mark or phrase that is used by someone else, the threshold issue, don’t use any kind of phrase that is connected in any way, shape, or form to another person/entity! Yes there are exceptions, such as adding distinguishing words, lettering, or designs and yes using the mark or phrase on products/services that are completely different from the trademark owners’ own goods is prudent. But taking a phrase that is widely recognized by the media, even if not actually used by an affiliated company on any kind of saleable items, is just asking for trouble especially if the underlying company has a long history and large war chest.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed