Earlier this week, Google announced that the company would be operating under a different banner: Alphabet. Some linguists have speculated that the driving force behind the name change is to prevent GOOGLE from becoming generic for search engine services. Becoming generic is the death knell for a trademark because it means that the mark is no longer a source identifier and does not point to the original owner, a critical function of trademarks. Practically, this means that the owner cannot stop others from using the brand on their own products. So how could a brand that is estimated to be worth $66 billion be in jeopardy?

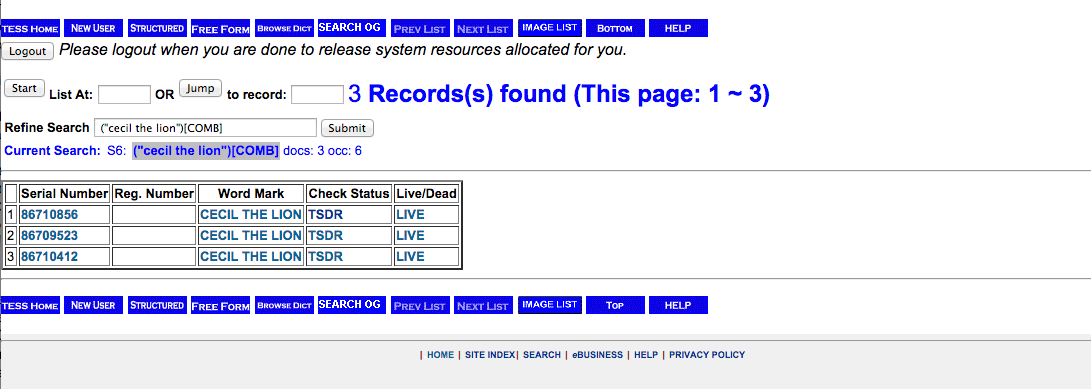

Whenever there is some major media event or news story (“Deflategate” or “Ice Bucket Challenge”, just to name a few), it always seems like there are enterprising people that are waiting in the wings to turn a quick profit off of the phrase. And what better way to get a nice tidy profit than to get a trademark on a phrase and secure that highly coveted monopoly giving you the power to emblaze the phrase “I Like Turtles” on every street corner in America? The latest phrase stems from Cecil, the lion that was killed by a hunter. Just within the past week, three different applicants have applied for registration of the phrase “Cecil the Lion”. If a trademark can be registered for any phrase, and the means for doing it are available (ahem, Legal Zoom), most people figure, “What the heck”. They are only out $500, and a monopoly on a phrase is certainly worth that much. Much like domain name opportunists in the late 1990s, where a person could snatch up names like “sofas.com” and “travel.com” for $10 or less and sell for millions, some people figure they can get the trademark and either leverage it themselves or license it to someone else.

Here’s the thing. The economics of such a strategy may not play out because there are real costs to getting and maintaining a trademark. Not only do you have to pay to file a trademark, you have to use the mark meaningfully in connection with a business in order to get the registration and maintain it. I venture to guess that many people who file a trademark application on the spur of the moment aren’t willing to put in the time to develop a bona fide business. Running a merchandising business (which is what most businesses surrounding an opportune phrase will be based on) requires a mastery of supply chain management, logistics, and marketing. This is definitely not a case of “if you build it [the trademark], they will come.” It also costs real money to monitor the mark, which will be necessary to keep exclusive rights in the phrase. Many people often underestimate these costs or, alternatively, the energy and man hours required if you choose to forego the traditional option of having an attorney find the infringement, review it, and send out the proper letter (never mind the costs of elevating enforcement action to the lawsuit stage, which happens more often than you might think). So you see trademark opportunism is only loosely related to domain name opportunism. At least with domain names the maintenance costs are low and you don’t need a business backing the domain name in order to keep it. Moreover, opportune phrases are often registered at the cresting of the wave of public awareness, which is a time when people are generally aware of the trademarked phrase. When the media frenzy involving the phrase dies down (which it usually always does), the trademark owner will be left with the responsibility of holding up the phrase and making sure it is still relevant or attractive to consumers. As for the “Cecil the Lion” trademark applications (each of which may pose conflicts to the other applied-for marks based on a likelihood of confusion), one may emerge victorious and may even go on to be a viable mark if the owners can figure out a way to monetize it. If they don’t make goods under the mark themselves, one could see such a mark being licensed to a zoo or non-profit organization that raises awareness about poaching through the sale of novelty items made in Cecil’s likeness (fortunately, you don’t need the permission of animals to make products in their likeness, like you would for people). So next time you get the itch to file an application with the trademark office, make sure to carefully consider all of the possible costs involved in both filing the trademark, and using it. This is not a definitely not a way to get-rich-quick. Counterfeiting at the Digital Counter – What Gucci and Hermes are doing to protect their brands8/3/2015

Having a fiancé that is in love with handbags (what woman isn’t?), I often find myself in-tow through the leather goods section of fancy department stores or stand-alone stores where Coach and Michael Kors bags are put on display like, well, Tiffany diamonds. Besides looking at the price tags and shuddering feeling the American Express card in my back pocket becoming a hot coal, I often think about the lengths that these companies go to in protecting their brand. Often times in the luxury goods market where there are many competing firms, all of which offer pretty much the same basic type of goods at the same price point, there isn’t much to compete on other than the name. Yes, product design is often a point of competition as well, but I’m trying to keep this post simple by only focusing on brand names. If you are a business that is competing primarily based on brand name, you are going to be more than a little concerned about how your brand name is used in the marketplace. One of the greatest examples of how companies obsess over their brand is the franchisor/franchisee relationship in the hospitality business (whether food or hotels). The main flagship brand is often the subject of dozens of pages of restrictions on trademark usage, including everything from product/logo display to partnerships with local community groups to promote the brand. The rationale for protecting a brand is no secret. If a brand name is the foundation of your business, losing it could mean losing millions of dollars in valuation and being forced to start over. Okay, those might be some extreme results (Thermos lost its brand to genericide but is still recognized as the market leader in insulated food/beverage containers, without which the world would be a much colder place), but the result is looming out there like a hawker of goods in a flea market and no brand owner wants to be positioned for failure in a hyper-competitive marketplace. And that brings us to the problem that many luxury brands are finding themselves in: tracking down and combating online counterfeiters. |

What is generic?A generic trademark or brand is a mark that has become synonymous with the name of a product or service, usually without the trademark owners' intent. As a trademark owner, you want to avoid allowing your brand to become generic. Avoid it like the black plague. Mr. Anti-Generic HimselfThe brains behind this online operation and namespace for, er, cool name ideas is Justin Clark. He is an attorney at the J. Clark Law Firm and plays a mad drum solo from time to time. Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

DISCLAIMER

THIS SITE IS ONLY A BLOG AND IS NOT MEANT TO CONSTITUTE LEGAL ADVICE. IT IS ALSO PARTIALLY AN ADVERTISEMENT FOR LEGAL SERVICES BY ME, JUSTIN CLARK, ESQ. BUT I AM NOT YOUR LAWYER AND YOU ARE NOT MY CLIENT. ALSO, THE PHRASE "MR. ANTI-GENERIC" IS MEANT TO MEAN INTELLECTUAL ENTHUSIAST AND IS NOT MEANT TO SUGGEST THAT I HAVE CERTIFIED OR OTHER EXPERTISE IN ANY PARTICULAR FIELD OF LEGAL PRACTICE. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed