So I noticed the same thing in intellectual property. In I.P., there are three different “buckets” (well four, if you count trade secret as a category). The buckets are “copyright”, “trademark”, and “patent”. Really innocuous words, right? Way more approachable than asset turnover random access memory (RAM), at least in my opinion. But still, there is all sorts of confusion (no pun intended) about what is what. What is capable of acting as a brand and what is capable of protection as a written work. You might have been subjected to this confusion over which I.P. is which, perhaps because you see the, TM, ®, and © symbols used seemingly interchangeably across different items. Sometimes the confusion can be taken to such extremes that multiple symbols are used simultaneously. Yep, just like what happened here, where the owner of a nut stand went nuts with using the official legal designations attached to the name of his product.

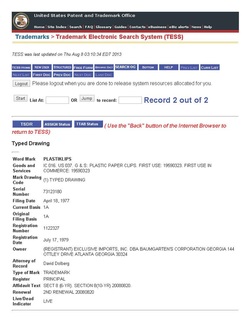

This news story about a Chinese company attempting to obtain a trademark on the word “Snowden” for a type of electric car with “top-secret” technology (which is where the Snowden name will come into play) is a further manifestation of the amalgamation of protections of I.P. under one umbrella. The article talks in one breath about how the company has applied for a “patent” and then in another breath it uses the word “brand”. Could it be a simple journalistic error or is it the result of a deeper confusion (no pun intended) about the true purpose of a trademark? This is not a post about “copyright vs. trademark” in the traditional sense and how to use each type of protection properly because there are already a gazillion of those on the net (and I’m all about originality!), including one from the USPTO itself. Instead, this post is more of a rumination on the tendencies for people to get confused about the purposes of legal protections. Now I’m not trying to be the grammar police here. I just want to understand what is truly going on in people’s minds when they confuse trademark, patent, and copyright.

It all comes down to this (essentially): anything that can designate a source for particular goods or services in the marketplace is a trademark. Anything that is an original, creative work of authorship (with some exceptions, such as actual ideas or useful things like tool designs and/or door handles, completely random, I know) is protected by a copyright. And patents protect useful, non-obvious and new inventions or discoveries including machines, methods of manufacture, or mixtures of things together constituting compositions of matter. Seems like pretty distinct categories, right? You have trademarks that protect symbols that have some kind of value in the marketplace (you use them as logos, connect them to products and services, and market them). Copyrights correspond broadly to works of art, which (on the whole) are completely different from symbols that are used in the marketplace. And patents deal with technical stuff. Simple enough.

But where does all the confusion as to the differences between trademark and copyright come to the fold? One point of confusion might be that symbols (such as the ubiquitous Mickey Mouse ears) may be associated with copyrighted works. So people see the mouse ears (which may not have the © or ®) and a movie instantly comes to mind, which most people easily recognize as a copyrightable work. Another point of confusion might be that logos (classified as pictorial work) are potentially copyrightable works, so people assume that (as a work of art) the logo gets copyright protection. It seems more difficult to trace the source of confusion over the significance of the word patent, but perhaps the confusion stems from the fact that anything that is proprietary is assumed to be exclusive, so someone may automatically think that something which was created by a company can be “theirs”, or otherwise it can be patented.

At the risk of creating even more confusion over the subject, certain objects can be protected by multiple types of I.P. For example, a shoe design can be protected by a design patent and can eventually be protected as trade dress (a type of trademark protection) if the shoe acquires secondary meaning (widespread recognition in the marketplace by a group of consumers). In fact, this is exactly what Disney is doing with its Mickey Mouse character: because the copyright on the original Steamboat Willy film is close to ending, Disney is now running a prominent portion of the clip before feature films in an attempt to turn the clip into a trademark. So now instead of being a creative work, the film clip has bridged the gap to become a useful symbol in the marketplace that can tip consumers off as to where the film that succeeds it came from.

At the end of the day, just remember this simple framework:

1. Trademarks are for things (words, designs, product packaging, sounds, even film clips) that can identify the source of where your product came from.

2. Copyrights are for written, designed, or theatrical works that were created by an author and are not intended to exclusively identify a source, at least in a commercially significant way.

3. Patents are for inventions or discoveries (not abstract ideas), but the kinds of things that require technical drawings, flowcharts, schematics, and prototypes to describe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed