Since writing that post, a prominent court (the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in California, a court that routinely deals with intellectual property law issues) handed down a ruling that gamers love but major organizations like the NFL hate. The case is interesting for the balance it strikes between protecting an individual’s right to publicity (which is distinct from protecting a person’s likeness) and protecting the first amendment interests of the public in being allowed to use authentic representations of characters in media. By looking at this balance, we can more clearly see what trademark law truly protects. Here’s a hint: it’s about more than just a dance.

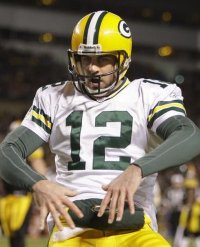

First, some ground work. Video games nowadays are pretty darn realistic. They have to be, right? After all, who wants to watch a bunch of pixelated blobs grunting up and down a simulated field that is a flat green polygon lacking any texture, with smaller pixelated blobs cheering in a sea of still more cheering blobs? That would just be lame. So game developers (to take advantage of faster computers and more robust graphics support) develop games with increasingly realistic graphics. E.A. Sports is no exception. In fact, in developing football games, E.A. sports sends out multifaceted questionnaires to NCAA and NFL team equipment managers in order to obtain information on a player’s equipment of choice. To obtain the rights to use the numerous logos, football stadiums, team colors, and of course the players in the games that EA produces, EA enters into licensing agreements with the NFL and NFL Players Association.

Brown’s main argument in his complaint against EA Sports was that EA’s use of his likeness in Madden NFL violated his right to his likeness and caused consumer confusion regarding Brown’s affiliation or status of endorsement of the Madden NFL game. To win on this claim, Brown needed to establish that his likeness was used in the game and that there was no artistic reason for including his likeness in the game. The artistic purpose goes to the First Amendment issue of requiring more commercial trademark interests to yield to interests in free expression. To evaluate Brown’s claims, the court had to weigh Brown’s interests against First Amendment rights because the underlying work (a video game) is an expressive work. ‘An expressive work?’ you might ask. Aren’t expressive works movies like Gone With The Wind and novels such as Huckleberry Finn? Well video games (like books, plays, and movies) are just as capable of expression as great a novella. Videos games include characters, dialogue, and music, after all. So you see, it’s a veritable smorgasbord of expression, just in the form of flashing LED lights.

The court applied a long-standing test to the dispute determining, first, whether using Brown’s likeness in the game had any artistic relevance. The court found that there was a great amount of artistic relevance (the threshold, as defined by the court is “zero”, whatever that means!) because the realism of the graphics in Madden NFL was so important to the central purpose of the game. The second prong of the test (which can be applied regardless of whether there is artistic relevance in having a person’s likeness appear in the work) is whether a person’s likeness is used to explicitly mislead consumers as to the source or the content of the work. Here, the court found that Jim Brown’s likeness was not used to explicitly mislead consumers because Brown’s appearance in the game or accompanying materials was not such that a player of the game would presume that Brown had endorsed the game in any way.

Artistic relevance is important when dealing with trademark usage in video games because courts do not want a game developer like EA to develop a game that uses a likeness of a celebrity (such as Jim Brown Presents Pinball) where the celebrity’s likeness is completely unrelated to the underlying game. You see, that would be an appropriation of the commercial significance of a celebrity’s image, which is the very thing that trademark law protects against. Without such an appropriation, all you have is a video game using your likeness as a representation of reality in order to make a video game experience more real. Protecting the first amendment interest in that work is more important than allowing a celebrity to hold a video game developer captive while a royalty check is collected.

This case is thus the perfect illustration of what trademark law is designed to protect: the prevention of consumer confusion as to the source of the goods, affiliation between a celebrity and the goods, or sponsorship. Celebrities can protect their likeness from appearing in media.... through the state law doctrine of right to publicity. Attempting to put a stranglehold on the use of materials bearing trademarks could put the kibosh on the ability to engage in free expression. The next test of this doctrine is whether video games that use real-life products (which may bear a trademark or be protected by a design patent) can pass as free expression protected by the First Amendment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed