Everyone is familiar with Monopoly. Many a family have bonded, torn each other to shreds, and reconciled over a game of Monopoly (sometimes even in a single sitting). It has been an icon of “game night” for years and has been the defining centerpiece of coffee tables and hallway closets for years. And as if that wasn’t enough to pique the interest of even the most bored-of-board game types, McDonald’s annual Monopoly promotion provides a delicious and addicting extension of the game. Elsewhere, you can find Monopoly branded slot machines, an all-purpose calculator, cuff links, and even bathroom fixtures and towels. That has to cover pretty much all bases.

Given all these marketplace identifiers, one would suspect that the brand MONOPOLY is a solid name and not subject to any kind of challenge, especially that the name is “generic” for any type of board game. The hallmark of a generic name is one that broadly identifies a category of products (in this case, board games that put players together in a quasi-free market to buy and sell properties), usually because consumers don’t know any other way to identify the product without using the name. Without ties to a single company as the source of a product, a generic name is available for general use by the marketplace.

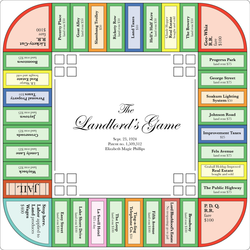

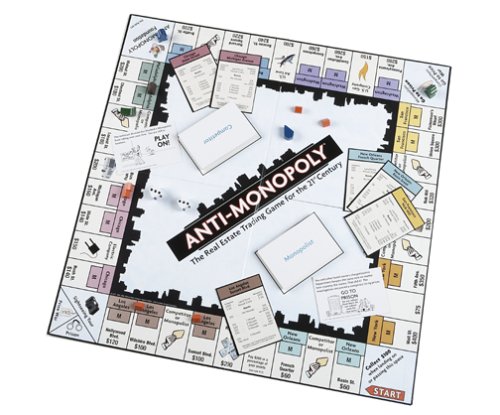

Yet that is exactly what a slew of court opinions found in the 1970s when an activist professor sought to name his board game Anti-Monopoly as part of a campaign to inform consumers about the ill-effects a monopoly could have on a marketplace. How could a brand with a 40-year history of success in the U.S. and abroad, with an exclusive hold as the identifier for a special type of board game be in doubt?

In his lawsuit against Parker Brothers to invalidate the MONOPOLY mark in 1974, Ansbach argued that the fact that Monopoly was generally known as “the monopoly game” in scattered circles of players across the U.S. demonstrated that the word MONOPOLY was generic for all property trading games. In essence, Ansbach argued that the name Monopoly was simply the name of a type of game, not affiliated with Parker Brothers. After looking over the record of evidence assembled by Ansbach and considering Parker Brothers’ own evidence regarding the origin of the name MONOPOLY, the court determined that the name MONOPOLY was not generic at the time it was registered because Ansbach had demonstrated that only a few people generally referred to the game as “Monopoly”. On the second question of whether the name MONOPOLY had become generic since its registration in 1936, the court found that MONOPOLY was a generic name because many consumers recognized MONOPOLY not as a name that identified Parker Brothers as the maker of the game but as the name of the game itself. The court made this determination using a modified standard of genericness: what was the motivation for a consumer to purchase a product and how did the consumer use the name to indicate this motivation. If the primary motivator is the product (i.e. a real estate trading game) and not the source (i.e. Parker Brothers), then the brand name is generic. To test such a question, the court had both Parker Brothers and Ansbach conduct surveys testing the reaction of consumers to the MONOPOLY name. According to the court, the name “Monopoly” was not a brand name to consumers because consumers asked for the game primarily by name only without inquiring further as to the maker of the game. Because consumers placed significance of the name as an identifier of a product and not as an identifier affiliated with Parker Brothers, the name MONOPOLY couldn’t possibly function as a source identifier. This conclusion was reached despite the fact that Parker Brothers had spent of millions of dollars on advertising MONOPOLY over 40 years and despite the practical requirement of consumers using the name “Monopoly” in order to purchase or play the game. Also, a separate survey conducted by Parker Brothers had found that 63% of consumers identified MONOPOLY as a brand name. Apparently, the court was not determined with the public’s perception of the name as brand identifier, only that consumers were not motivated to buy a product primarily based on the brand name.

And just like that, the name MONOPOLY ceased to be protectable as a trademark. Competitors could develop their own property-trading games and call them “Monopoly”, and professor Ansbach could continue selling his Anti-Monopoly game without fear of being shut down or having to pay a royalty to Parker Brothers. At least for awhile, there was no monopoly on the word MONOPOLY.

But there was a furious backlash both by legal scholars and other companies who feared that the court’s ruling against Parker Brothers could be used to justify the invalidation of any brand name if consumers didn’t know the identity of the company that made it. Competitors would be able to free ride on the goodwill in a particular name simply by showing that consumers were well aware of the name and its connection to a specific product, but not to the owner of the brand. The Supreme Court denied to take on an appeal of the case leaving Parker Brothers to petition Congress to amend the trademark laws on the topic of when a mark becomes generic.

Under the Trademark Clarification Act of 1984 updated the definition of trademarks that were not eligible for cancellation to include marks that were distinctive, but which nevertheless were commonly used by consumers to identify a unique product or service. Also, as to whether a name had become generic for specific products or services, the primary significance of the name to the relevant public was the deciding factor, not the purchaser’s motivation to buy a product. Had this new standard been used in the Anti-Monopoly case, it is likely that Parker Brothers’ would have prevailed because consumer understanding of the name MONOPOLY was that it referred to one specific game from a single maker, not a type of game available for purchase from a variety of sources.

Although the Trademark Clarification Act was passed largely in response to lobbying by Parker Brothers, it could not be applied ex post facto. This didn’t stop Parker Brothers from taking back its status as exclusive owner of the MONOPOLY mark under an agreement with Professor Ansbach that declared the MONOPOLY name a valid trademark and let Ansbach continue using the Anti-Monopoly name under license from Parker Brothers. Hasbro has since acquired the name MONOPOLY and continues to assert its monopoly over the name.

This story serves as an indicator of the distorted results that courts can sometimes bring to disputes that seem on the surface to be obvious. Indeed, while most consumers understood the MONOPOLY name to be a brand name, probably for a particular game, the court didn’t saw the association as one for a particular type of game. Even in all the madness and confusion that is a court opinion, a near death experience for the MONOPOLY brand offers lessons for all brand owners, even those that are not powerful enough to lobby Congress and get the kind of reversal that Parker Brothers did. First and foremost, a brand owner must understand the associations that consumers are making between the brand name and the owner. In the age of the Internet, consumers can come to play pretty fast and loose with a company’s trademark using it as a verb or shorthand in conversations or product reviews. Even if a company only makes a single product and the company’s brand name that dominates the market, the company can and should make sure that consumers associate the brand name used on that product with the company, or that they at least recognize it as a brand name. Companies should also carefully monitor the marketplace for competitors who might be using a similar name to that the original company uses, or news media that are gung-ho on using certain buzzwords to stir-up their audience. While the dominance of a single name can be valuable, the owner of the name should make sure that its consumers really are referring to that company’s specific product when they use a name, not the product itself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed