As you may remember from the previous post, we left off with the rumination on whether the government could restrict all uses of government insignia, whether for commercial or political purposes. Some agencies appear to allow some use of their insignia to be used on t-shirts and other items. NASA is one notable example, and this fact is evidenced by all the NASA-related insignia you find on websites and in stores like Target. Other governmental bodies (like the State of Nebraska) seem to limit most commercial and political uses of the state seal or any deceptively similar images. The rationale behind such restrictions (at least from the standpoint of the government) is that commercial use of the insignia is likely to confuse consumers in the marketplace as to the affiliation between a governmental body and the maker of the t-shirts.

“No person may, except with the written permission of the Director of the National Security Agency, knowingly use the words “National Security Agency”, the initials “NSA”, the seal of the National Security Agency, or any colorable imitation of such words, initials, or seal in connection with any merchandise, impersonation, solicitation, or commercial activity in a manner reasonably calculated to convey the impression that such use is approved, endorsed, or authorized by the National Security Agency.”

Preventing confusion is all well and good, even if the government is trying to do it by fiat. I mean, after all, nobody wants everyday civilians showing up at a bookstore wearing shirts bearing the NSA seal and demanding that the manager turn over all the sales records for certain customers in the hopes of finding a terrorist sleeper cell. That would be a form of confusion that might be reasonable for the government to want to prevent. But there are other laws on the books that punish that kind of behavior, right? Of course there are. See here. (“Whoever falsely assumes or pretends to be an officer or employee” of the federal government is in deep you-know-what; I’m paraphrasing of course).

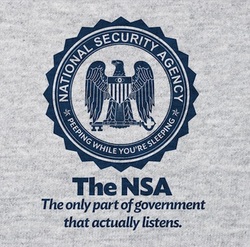

Lets just take it as a presupposition that no one will be confused about a parodied NSA logo that includes the bi-line “Peeping While You’re Sleeping”. This is a clearly critical phrase designed to evoke the recent spying accusations against the NSA and its phone surveillance program. Most people would probably recognize that. Would the NSA do itself wrong like that, make itself an object of criticism and use it as a public-service announcement to drum up support for its programs? It doesn’t take a Madison Avenue marketing expert to answer “no”, I’m sure.

Clearly, such use does not appear calculated to convey the notion that the NSA is in any way connected with the merchandise that bears the tagline. Simply using the name of an organization or company in the context of a complaint or tongue-in-cheek remark is not something that creates confusion as to association because to be most effective, a criticism often must identify the subject object being criticized. Negative consumer commentary against private companies has been labeled as protected speech that is at the core of the First Amendment. Giving any organization the right to shut-down all critical messages that included a trademark or insignia of the organization would, of course, make every organization a sacred cow. So this is why the Lanham Act does not apply to non-commercial speech involving the use of a third-party’s trademark. Practical applications of this principle include a website whose sole reason for existing is for disgruntled consumers to voice complaints against a corporation (the blogger page using the title “walmartsucksorg” in the sub-domain is one such non-commercial use).

In the case of a parody, however, the intent of the person using the mark is to amuse, not confuse (sounds like a slogan, doesn’t it?). The danger of confusion drops if a consumer recognizes that the subject of the parody did not actually offer the goods being used with the parodied mark. This is the essence of parody: the broadcasting of two different messages speaking to the original (the trademark owner) but also demonstrating that the parody is not the original. Therefore as a parodist, the goal is finding that “sweet spot” between trademark infringement and creating a completely unidentifiable joke. A good parody will bring to mind the trademark owner but add just the right amount of a distinctive “twist” in the form of humor or irony that a consumer would be able to tell the difference. If your parody can do that, make all the t-shirts, coffee mugs, and skateboard decks that you want because use of the trademark in the parody (even if for a commercial use) is also protected as a kind of critical speech.

I think the value of parody only goes up when the parody is rooted in a more general message about the government because government criticism is at the core of the First Amendment. Whats more, there seems to be little-to-no likelihood of confusion as to the affiliation or connection between the message and the government if the critical statement involves some sort of irony or over-dramatic statement. These kinds of critical statements would certainly be protected in a non-commercial setting, so why should the calculus be any different when the parody has some kind of commercial application? If there is no likelihood of confusion and consumers understand that the message is clearly not tied to the trademark owner, what harm is there in allowing the parodist to commercially exploit a clever political statement?

If a private company would have trouble preventing a third-party parodist from using a trademark in-jest to make some kind of overarching statement about the company, why should the government be allowed to prevent third-parties from creating parodies out of official government insignia?

Because this post has again gotten remarkably long (if anybody is still reading!), I will take up this question next time in the third (and final) installment on this topic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed