To really answer this question, it helps to understand this maxim: the essence of a trademark is source identification. Always has been, and always will be. Even in the face of technology, which always seems to be pushing the envelope of how a company can truly engage a consumer, trademarks must maintain their source identifying capability. The beauty of the statutory definition of a trademark is that there are no restrictions on the form of the trademark, just so long as it serves the purpose of source-identification (and usually nothing more). For example, there is no statute or public policy that requires trademarks to cater exclusively to one of the five senses; any type of identifier that can be discerned by consumers is fair game for a trademark. This gives companies a lot of freedom in defining their brand. Given enough creativity and vision, a company could be quite unique in their branding endeavors.

Apple has always prided itself on fusing form with function, for example, creating a mouse as a component for users to operate the computer. A more modern example is the use of a single button on the face of the phone, a decision apparently born from Steve Jobs’s phobia of buttons. Also, Apple’s sleek iPhone design may make the phone itself more visually appealing for the same reasons that all other Apple products are attractive: they like simple, sleek design embodied through metallic casings, glass, and monochrome color options. But the choice to follow minimalist design principles and include (or exclude) certain design features is not a choice that results in a feature that can identify Apple as the source of the products that contain the design. Minimalist design is a school of thought not owing its origin to any particular company. As a school of thought, any other company is free to design their products according to the teachings of the school. In a word, minimalism is not distinctive.

Another mainstay of Apple is the principle of form follows function, or the rule that the shape of an object should be primarily based upon its intended function or purpose. This appears to be a corollary of one of Apple’s core design principles: products should be designed for the people that will be using it. Notice that this principle doesn’t necessarily put the functionality of a product on a pedestal to the exclusion of all other considerations. Instead, the design of a product itself (including user interfaces, product packaging, and any messaging delivered by the product) is one of the driving forces behind the choice of making one component a certain shape or choosing to make the product casing rounded. Even with the injection of design considerations into the overall engineering process, a company could still focus too intently on the end-goal: making a product more usable. Design features that are included solely for usability reasons means the particular features cannot be trademarked, no matter how much a company is known for such designs.

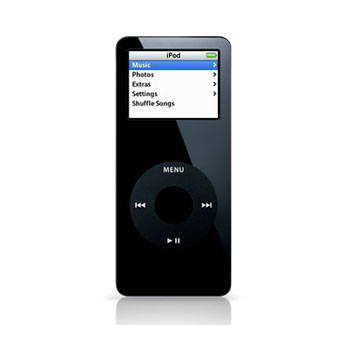

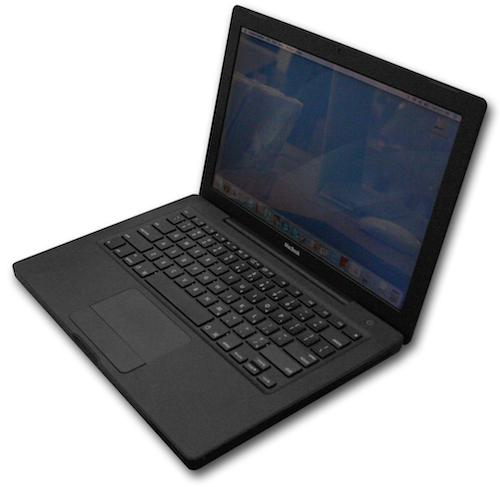

There’s no question that Apple engineered these design elements and hit on something brilliant with consumers. The fact that Apple had used similar design features on other products like the iPod or MacBook was not enough to make the features source-identifying, especially where a significant part of the appeal of those features was their usability.

The lesson seems to be that a company should be mindful of overreaching when they design their products and define which elements are to be protected as trade dress. Paradoxically, even though it can take years of use in commerce before trade dress is recognized as a protectable trademark, the validity of trade dress itself can be impacted at the earliest stage of the design process.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed