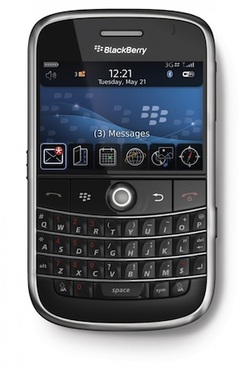

When most of us were kids, we were told not to say certain words. We were admonished that these words are “bad” and that if we used them, evil things would pay us a visit and we could even end up with soap in our mouths. When we grow up, there are plenty of bad words too, although the list of bad words may not be the same as it was when we were kids. Well it wasn’t too long ago that “BlackBerry” was a bad word. It symbolized obsession and workaholism, that constant urge lurking at the back of your mind like the guy in the back alley who knows you have an addiction. Indeed, the impact of the BlackBerry devices on people’s lives was so significant that it earned the not-so-glamous mantra of “crackberry”, a not-so-subtle reference to the fact that a BlackBerry device is as addicting as a drug.

No, I’m not saying that blackberry is in fact a bad word, but it did almost go the way of becoming one in trademark owners’ and lawyers’ minds.

Let me do some explaining before you tell me to wash my mouth out.

In legal parlance, the parlance for this state of trademark decay is “going generic”. Its pretty much the death knell for a trademark, unless the trademark owner can figure out how to convince the public that a particular mark is not generic.

Many generic names are well-known in the lexicon of attorneys. It seems slightly ironic that some names that lawyers are close to simply because the device that the name is attached to is a useful tool for lawyers have almost become generic themselves. Xerox is a big one. Dictaphone (for dictation equipment, commonly used by lawyers to punish secretary’s with monotonous letter-writing instructions) is another. And BlackBerry could have been next.

BlackBerry as a company warrants little background discussion and the reader will probably not argue that BlackBerry was the first maker smartphone manufacturer to make a widely-used multi-function cellphone. For a period of years, it dominated the entire high-end phone market. While other companies rose up and attempted to best BlackBerry’s Devices, Apple was the first company to knock a chip off of RIM’s statutory of enterprise system cellphone dominance. Then Samsung gained some ground on the old stalwart. Today, BlackBerry doesn’t quite have the same stranglehold on the market as many other smartphone makers. There are more competitors and more competitors mean additional brands in the marketplace competing for more dollars. With more options, consumers won’t feel compelled to refer to any email and web-enabled device as a “blackberry”.

This prompts an ironic observation: a brand that is in danger of becoming the generic name for a product can migrate out of the danger zone of genericism and back into the green zone of trademark protection through the process of the trademark owner becoming obsolete. As one commentator put it, the Blackberry trademark has become a victim of its own success. How strange and counterintuitive. Is Blackberry really a victim in this case? Their trademark, how connected with less-popular products, is not dead completely. It still represents millions of dollars of goodwill because it is connected with a not-so-insubstantial user base. It represents to many business users the source of an enterprise-level email juggernaut, a system that first made business email seamless.

The BlackBerry trademark, while connected with a product that today is being left in the dust by competitors, is by no means obsolete. After all, the cellphone market is extremely fluid because many advances are based on technological advancements in functionality, advancements which are often driven by the demands of users of the device. What BlackBerry represents to many could be just as valuable the year that the company releases a nuanced and unprecedented product that serves the same goals and satisfies the same demands that BlackBerry set out to meet all those years ago when it built its enterprise email system. The trademark surely has value if it is acquired by another company. An analogue can be found in Apple’s threatened obsolescence during the 1990s when Windows appeared to be the de-facto manufacturer for personal computers. The Apple brand for personal computing seemed to be down for the count.

We all know the story from there. Apple released its iPod, then the iPhone, and then the iPad. The brand was revitalized almost as though being brought back from the dead. Far from being generic, Apple is a veritable brand juggernaut. So just as BlackBerry, having been in danger of becoming generic, has become seeming obsolete as a brand today, any resurgence by the company could bring the brand back to relevance. And when that happens, all the goodwill that the brand had acquired by virtue of substantial marketing and consumer recognition will make the brand that much stronger.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed